flowchart TB

subgraph vitro [In vitro]

direction TB

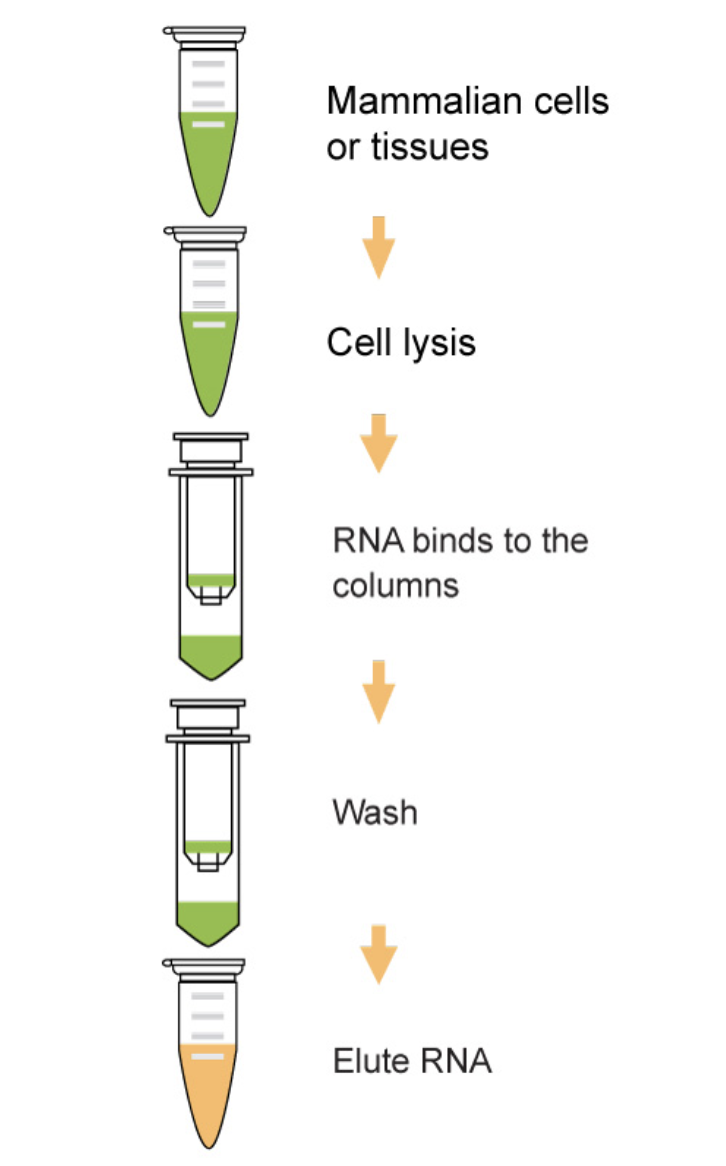

A(<font size=6>Isolate total RNA) --> B(<font size=6>Enrich a specific type of RNA)

B --> C(<font size=6>Prepare the RNA sequencing library)

end

subgraph silico [In silico]

direction TB

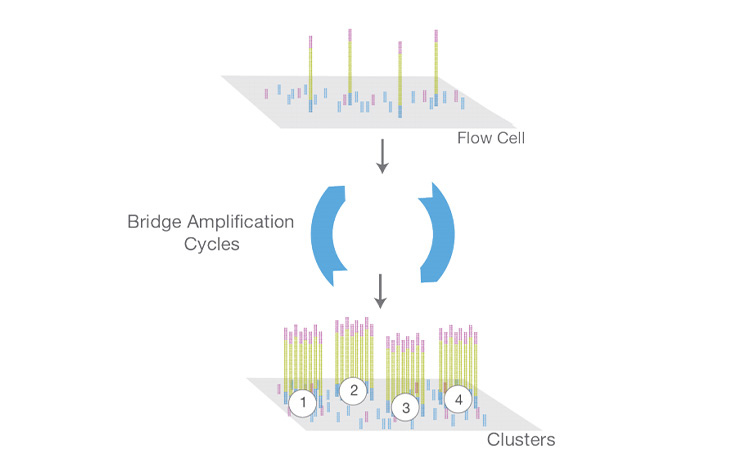

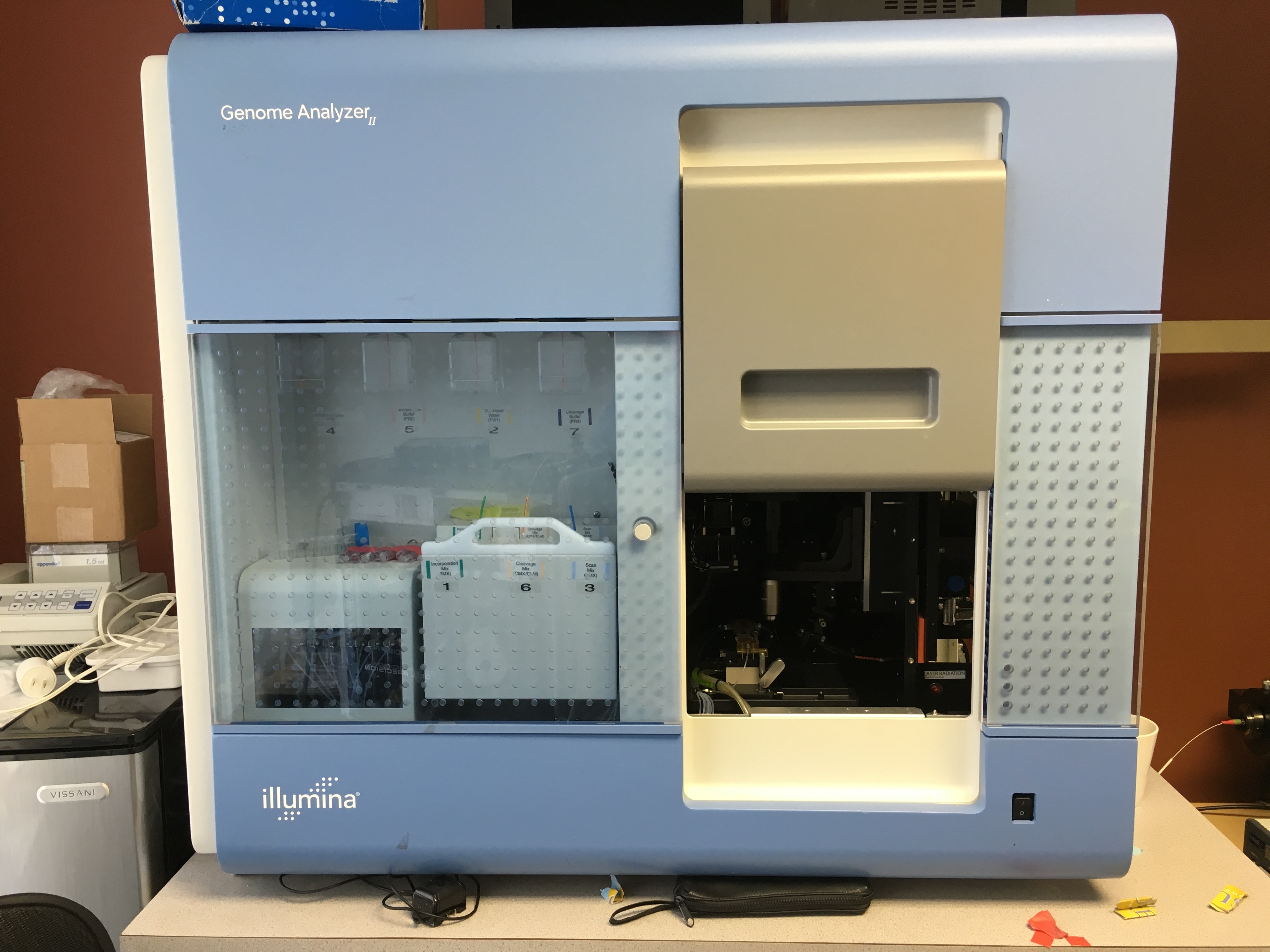

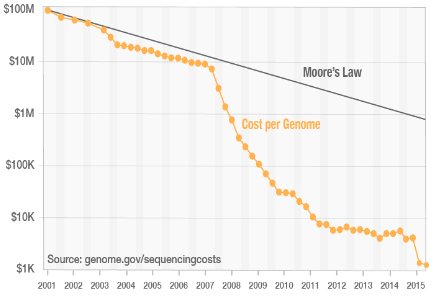

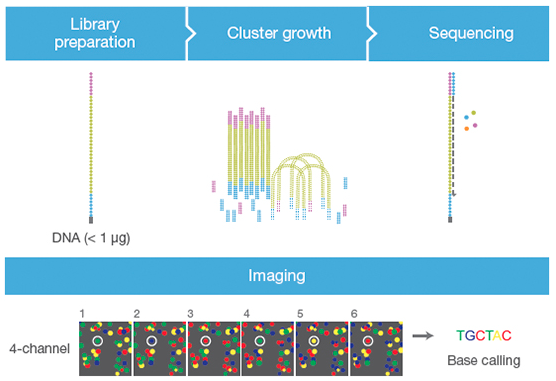

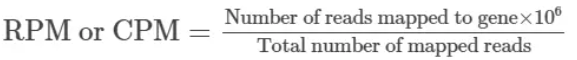

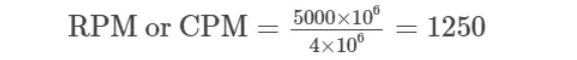

D(<font size=6>Sequencing) --> E(<font size=6>Quantify expression)

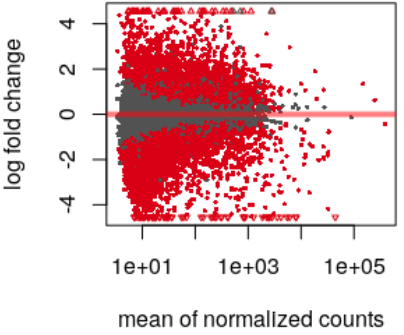

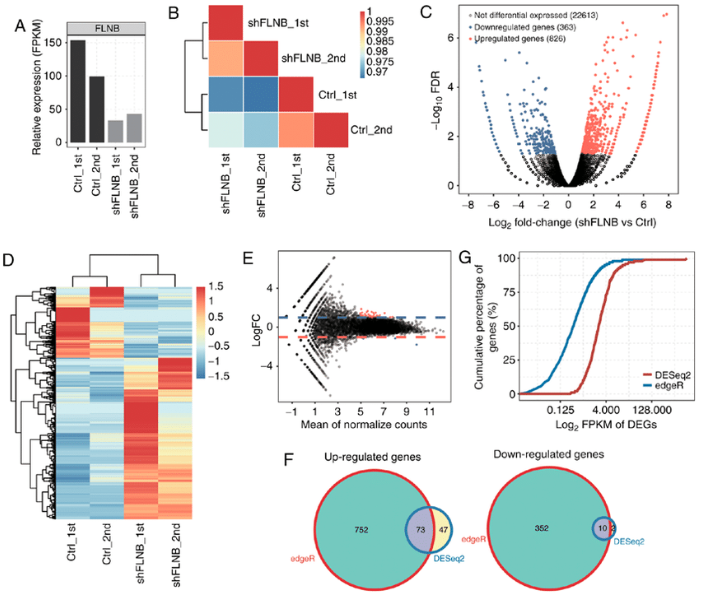

E --> F(<font size=6>Differential Expression analysis)

F --> G(<font size=6>Biological conclusions)

end

vitro --> silico

classDef className fill:#D1D1D1,stroke:#333,stroke-width:1px

class A,B,C,D,E,F,G className;